Re-Imagining History

Vast swathes of the Amazon jungle were planted by the pre-Columbian civilizations who lived there. The formidable forests navigated by the first settlers in the eastern United States had in fact long been managed through controlled burning. Similar fires may have created and maintained the Great Plains, which for hundreds of years hosted a vast civilization with outposts right here in Kansas City.

These are but some of the varied ways Native Americans shaped the landscapes and wildlife encountered by the first Old World explorers and pioneers—and continue to shape our world today.

Yet for generations, most us have been taught otherwise. Western films depicting headdress-wearing Indians in dramatic shootouts with stoic cowboys; tales of intrepid frontiersmen like Davey Crockett, Daniel Boone, and Lewis and Clark; horrific descriptions of humans, children, being sacrificed to pagan gods; scenes of covered wagons trudging endlessly westward along the Oregon trail; these have long captured our national imagination.

While there are shades of truth in these stories, it is imperative to acknowledge that these rather are one-sided accounts, leaving out a great deal of the story and owing themselves entirely to one of the darkest episodes in human history.

Cultural Powerhouses

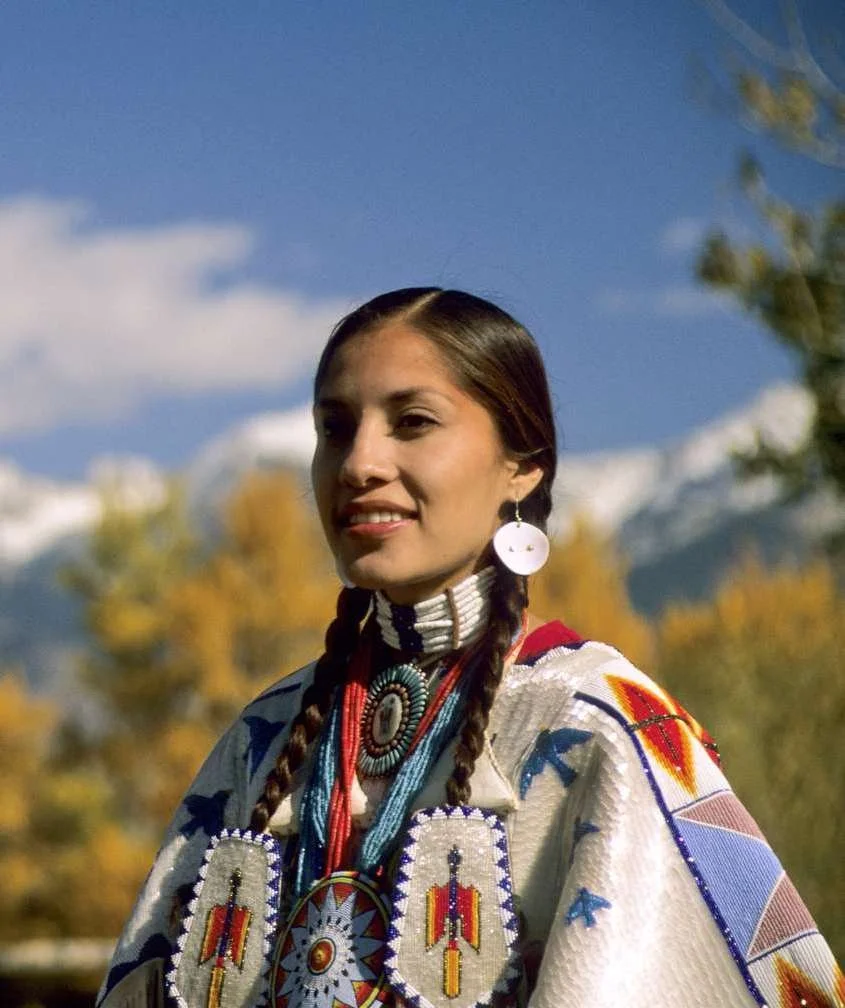

It is estimated that in 1492 AD, the year Columbus landed in present-day Cuba, the population of the Americas numbered between 60 and 100 million people—greater than that of Europe. These people were as diverse as they were numerous; over 400 known nations and tribes occupied North America alone. Native Americans, particularly equestrian Plains tribes, were often taller than Europeans and white Americans, averaging around 5'8", due to excellent health from good nutrition and lifestyle. Many tribes were matrilineal, meaning children belonged to their mother's family as opposed to their father’s as practiced today. Women often held significant roles in society:

Important religious and political leaders

Owners of dwellings and tools (but not land, as the concept of land ownership was different)

The size, economy, engineering, and scientific knowledge of many American cultures is staggering. With a population between 200,000 and 400,000, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan was comparable to the greatest European cities of its day. Built entirely on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, the city was connected to the mainland and surrounding islands by a complex system of bridges and canals, such that every section of the city could be visited either on foot or via canoe. A number of large temples, towering over the surrounding city, perfectly imitated the distant mountains that dominated the skyline.

“When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land we were amazed... and some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream? (...) I do not know how to describe it, seeing things... that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about.”

In North America, meanwhile, interactions between indigenous people and the European intelligentsia and upper classes fueled a cultural and intellectual revolution now known as the Enlightenment. Feminism, the concept of human rights, and even democracy are deeply rooted in Native cultures throughout the Americas, but particularly North America. Indeed, our representative democracy here in the United States was inspired in no small part by the government system of the Haudenosaunee League, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy.

The early colonial period of the United States is full of accounts of colonists choosing a Native life rather than returning to their kinsman, summarized here by Benjamin Franklin:

“When an Indian child has been brought up among us... if he goes to see his relations and makes one Indian ramble with them, there is no persuading him ever to return. [But] when white persons of either sex have been taken... and lived a while among them, tho’ ransomed by their friends, and treated with all imaginable tenderness to prevail with them to stay among the English... in a short time they become disgusted with our manner of life, and the care and pains that are necessary to support it, and take the first good opportunity of escaping again into the woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them.”

Meanwhile, in the Andes mountains of South America, the Inka - a socialist empire with no metal, glass, wheel, or writing system - was the largest and most powerful empire on earth. They experienced low levels of hunger and theft, and through their understanding of ecology could farm tropical crops on mountain peaks. Like the ancient Egyptians and Greeks, the Inka civilization was already ancient in its own eyes; many of its cities and earthworks had been constructed on the foundation of yet older empires, lost to time.

“We found these kingdoms in such good order... The lands, forests, mines, pastures, houses and all kinds of products were regulated and distributed in such sort that each one knew his property without any other person seizing it or occupying it, nor were there law suits respecting it… they were so free from the committal of crimes or excesses... that the Indian who had 100,000 pesos worth of gold or silver in his house, left it open merely placing a small stick against the door, as a sign that its master was out. With that, according to their custom, no one could enter or take anything that was there. When they saw that we put locks and keys on our doors, they supposed that it was from fear of them, that they might not kill us, but not because they believed that anyone would steal the property of another.”

A Great Dying

Then, catastrophe struck.

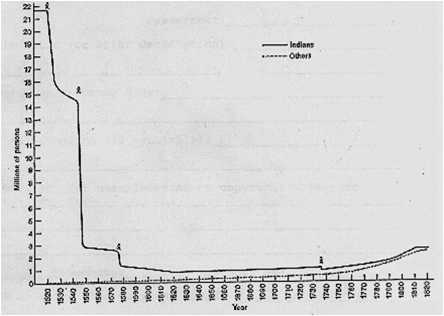

Over the course of a few generations, between the 17th and 18th centuries, a series of devastating plagues—in combination with resettlement, famine, enslavement, infighting, and warfare—killed anywhere from 15 to 100 million people.

This amounts to 90% of the population of the entire western hemisphere—and 10% of the world’s population. Such was the scale and speed of the dying and that it led to a prolonged period of global climate change called the “Little Ice Age”.

The cultures and histories of these people—often passed down orally, as many had no written language—vanished, just as abruptly as the people themselves, leaving behind mere fragments and incomplete teachings.

Yet what little remained was often of little interest or value to European historians, anthropologists, or archaeologists. In the best of cases, colonists tended to doubt the accuracy or legitimacy of such systems. In the worst of cases, people intentionally worked to erase and de-legitimize these accounts, even going so far as to destroy evidence of their existence. This contempt was not limited to scientists, but institutional; it extended into all classes and levels of society, from farmers, to politicians, to merchants, to religious leaders, and everyone in between.

Later generations encountering uninhabited forests and plains filled in the gaps left by Native Americans with their own ideas and theories. They often started with the assumption of European cultural and intellectual supremacy. It was inconceivable to many minds of the time that bands of primitive savages, so easily conquered and laid waste by European conquerors, could have once sculpted entire regional landscapes, at a similar scale as the mighty, refined empires of their ancestral lands.

Yet far from virgin lands undisturbed by mankind, the captivating expanses witnessed by explorers are a result of concurrent, widespread, catastrophic civilization collapse.